Training and the menstrual cycle

Now that we have covered the menstrual cycle and you are hopefully feeling more comfortable with the different terms surrounding it (if you missed it then I suggest giving it a quick read before this 🙂), we can move on to how, or if, any of this actually makes a difference to our training.

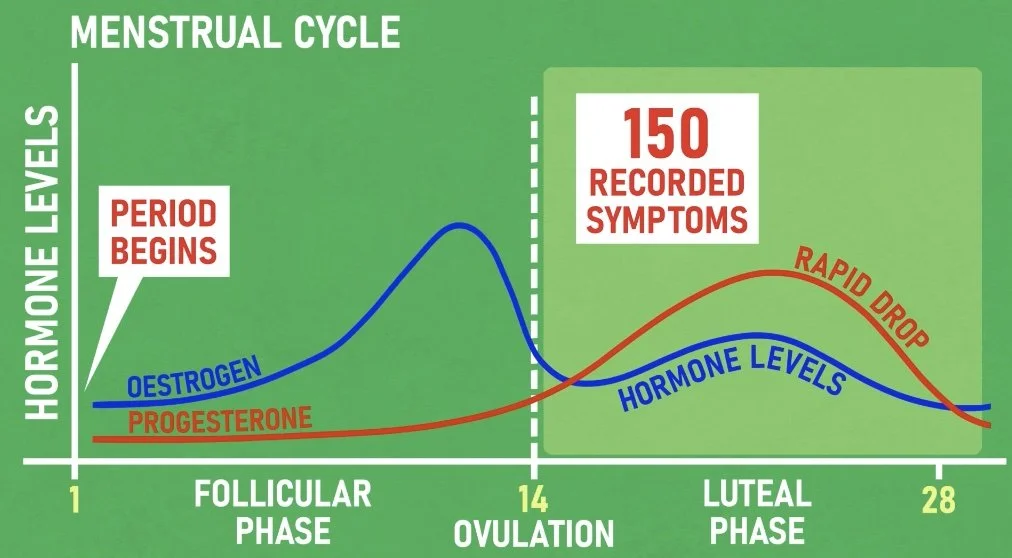

Here is a diagram to remind you of the various phases and hormones before we start:

Whilst for some people exercise can help to reduce period symptoms such as cramping there are many women who report that period symptoms can greatly hinder their ability to exercise.

According to one survey, 60% of British sports women said their periods affect their athletic performance (BBCsports, 2020). So, in what ways does the menstrual cycle negatively affect women when it comes to training - and are there any positives?

Well, there is evidence to suggest there might be an increased chance of strength gains during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (when oestrogen is high and progesterone is low).

A study carried out by sports coach Guy Pitchers and Prof Kirsty Elliott-Sale into the performance of female athletes looked at women who either strength train only during the follicular phase or only in the luteal phase.

They found that the women who were training in the follicular phase had a significant increase in muscle diameter in comparison to those who were only training in the luteal phase.

This conclusion is supported by a study that found women who strength-trained frequently in the first half of the cycle and less frequently in the second, saw 14-40% more strength gains than when their training was carried out evenly across the cycle.

However, as with most research in this area, the number of participants is often small, making it impossible to draw any definitive conclusions. A big reason for low participant numbers is that the menstrual cycle affects every woman differently and it is therefore hard to apply a ‘one size fits all’ approach.

There are other factors to be taken into account when considering the menstrual cycle and training.

One example is that during the Luteal phase, when progesterone levels are high, a woman’s core temperature will start to rise - although there is little evidence to suggest this has an effect on women’s overall body temperature during training.

The body is also less able to use carbohydrates as fuel for exercise so can find it harder to work at higher intensities. During this phase the body prefers fat as fuel, which might make lower intensity aerobic training more suitable.

During the follicular phase, the higher oestrogen levels make a good environment for high intensity training as recovery is quicker and the motivation to train may be higher. Oestrogen is also regarded as a feel-good hormone as it increases levels of serotonin.

This means motivation to exercise may be higher, plus our body is better at protecting against muscle damage, reducing inflammation and speeding up recovery time. All of this suggests physiological benefits of strength training and high intensity exercise during the follicular phase.

As discussed in my previous post, progesterone can have a calming effect on the brain and help with sleep, making this later part of the menstrual cycle a good time to recover from training.

However it is also a catabolic hormone which means it breaks down muscle. The sharp drop in serotonin can also have a negative effect on mood, heightening negative feelings towards ourselves and to exercise. Taking all of this into account it may be more difficult to build muscle and strength towards the end of the luteal phase..

Despite all of this, McNulty (2020) analysed 51 studies and found that “female’s performance capacity (endurance, speed and power) are not likely to be affected by hormone fluctuations during the cycle.” However it is worth keeping in mind that there is very little good quality research looking to understand the relationship between the menstrual cycle and athletic performance.

This means that on any given day of our menstrual cycle we should be able to perform at our best. However, what is affected by hormone fluctuation is our emotional and physical state. If we are not at our peak emotionally, performing at our best can feel a much bigger task than when we are feeling mentally motivated.

So, how to conclude something that seems inconclusive?? Well, what we have found is that the change in hormones throughout the menstrual cycle is very likely to have an effect on our motivation to exercise and our ability to recover.

While it does not seem beneficial to completely change your workout routine depending on your cycle, we can educate ourselves about the possible scenarios that may arise.

Preparing yourself in this way can help explain behaviour changes that we may otherwise blame ourselves for.

So, next time you are lacking in motivation to get to the gym, consider where you are in your menstrual cycle and what could be causing this change in mood.

If you feel like this is you, are there extra measures you can put in place during this time of the month to make sure you can keep showing up for yourself?

One thing is for sure, you will be able to dominate your workout regardless of your menstrual cycle but remember to cut yourself some slack.

Constant hormonal fluctuations are not easy and affect us all on varying levels. Be aware of your menstrual cycle so you are ready to overcome any challenges when it comes to training.